The Hokule’a project’s ongoing legacy for Native Hawaiians

1999 on the voyage to

Rapa Nui (Easter Island)

Sam Low stands in awe of his ancestors — and he isn’t alone. “They possessed ships that were capable of traveling the world,” says Low, an anthropologist, filmmaker, photographer, and lifelong sailor. For millennia, his Hawaiian forebears ruled the Pacific, along with other Polynesian and Pasifika peoples, as they made purposeful voyages of discovery.

Low is one of the principal historians documenting the creation and continuing voyages of the Hokule’a (“Star of Gladness”), a re-creation of the Polynesian voyaging canoes that made possible the intentional settlement of hundreds of islands widely scattered in that vast ocean. Significantly, the achievement disproves the theory promulgated by Norwegian author and ethnographer Thor Heyerdahl and others that these ships simply drifted with the wind.

The Hokule’a project has also inspired a renaissance of Native Hawaiian culture and a justifiable pride on the part of Hawaii’s Indigenous people. After all, the project clearly demonstrated that these 60- to 70-foot-long doublehulled ships and the navigators who found their way — “wayfinding” — through the trackless sea are examples of traditional Indigenous sciences at their best.

Wayfinding a Renaissance

traditional navigation

methods (above) and

trains others.

In the early 1970s, Native Hawaiian culture was at a low point. After nearly two centuries of colonization, Native Hawaiians were at the bottom of the economic ladder, with scant cultural moorings. The Hawaiian language was in decline, and traditional ceremonies were scarce. Some even say that the culture was nearing extinction.

But that dire situation ended in a dramatic turnaround through the voyage of the Hokule’a. The project was close to the heart of Herb Kawainui Kane, a founder of the Polynesian Voyaging Society (PVS). “Herb’s pure vision of building the double-hulled, double-masted Hokule’a brought back the realization by the Hawaiian people that they were ‘Children of the Long Canoes,’” says AISES founding member Al Qöyawayma, who holds patents in inertial guidance systems. His interest in high-tech navigation and Kane’s interest in traditional navigation led to a close friendship that lasted until Kane’s passing in 2011.

Kane became intrigued with traditional oceangoing technology as a child, growing up in his native Hawaii and Wisconsin. An artist and sailor, Kane accumulated every visual clue he could about what his ancestors’ ships looked like, then created paintings depicting those ancient vessels and the people who steered them. Kane’s paintings stirred the imagination of others who felt the call to revive one of the Indigenous world’s greatest scientific achievements. Other PVS founders with the vision to build the first voyaging canoe in 600 years included Tommy Holmes, a writer and waterman, and Ben Finney, an anthropologist. With their support, Kane designed the original Hokule’a, named for Arcturus, one of the most important stars in Polynesian navigation.

Setting Sail with a Mission

of the community after arriving

in Mauna Loa, Oahu.

“The Hokule’a’s voyage had three missions,” Low says — in science, culture, and traditional knowledge. The scientific mission was to demonstrate that these wooden vessels, constructed by a society that possessed no metals, could navigate with cargo and passengers through the Pacific to specific destinations.

The founders also intended that Native Hawaiians reclaim their navigational heritage. After building the canoe and fine-tuning its distinctive triangular sails to catch the trade winds, the PVS needed a traditional navigator, trained almost from birth to steer the ships. Because there were no more Native Hawaiian navigators, master navigator Mau Piailug, from the Micronesian island of Satawal, was recruited. “Mau represents the spirit of exploration and the deep understanding of the science that was passed on for about 1,000 years,” Low says.

In 1976 Mau guided the canoe southeast from Hawaii into Papeete Harbor in Tahiti. There the crew was greeted by a crowd of more than 17,000 people, writes Nainoa Thompson, a student of Piailug from a traditional family on Oahu. Today, Thompson is a master navigator in his own right and trains other navigators to carry on the legacy. He is also one of the leaders of both the PVS and the Native Hawaiian renaissance

The second mission — cultural revival — dovetailed with the stunning success of the science mission. “When the Hawaiians saw those ancient sails on the horizon, they began to wonder why they didn’t learn in school that they were the world’s greatest navigators and what else they hadn’t been taught,” says Low. “It was the beginning of the Hawaiian revival.”

Hawaiians began to seek out aunties, uncles, and the remaining cultural practitioners to relearn what colonization had tried its best to wipe out. Today, the Hawaiian language is taught in both public and private schools. Traditional halau (hula schools) impart the importance of hula to the culture. And a resurgent sense of pride in their heritage is reaching Hawaii’s sons and daughters wherever they may live.

The third mission — traditional knowledge — continues as the Hokule’a and its sister ship, the Hikianalia, traverse the world’s oceans (you can follow the voyages at hokulea.com). The ships and their crews take Indigenous knowledge and respect for nature and share it to preserve the oceans — and the Earth.

To showcase the history and ongoing legacy of Polynesian sailing science, Low, who crewed on the Hokule’a during three voyages, wielded his filmmaking and photography skills to create a 1983 Public Broadcasting Service documentary, The Navigators, and a 2013 book, Hawaiki Rising

Steering by the Stars

she has much to learn about navigating.

Ka’iulani Murphy has been absorbing all she can about navigating the Pacific — and she has a role model. After all, she says, one of the first voyagers in Hawaii was the goddess Pele. “Nainoa was one of my first mentors,” says Murphy, who has made several voyages on the Hokule’a. “The wa’a (canoe) is so inspirational.” Murphy also studies under navigators like Bruce Blankenfeld, and she has learned sailing skills from longtime crewmembers, including John Kruse, Billy Richards, Snake Ah Hee, and Mel Paoa.

And there’s a lot to learn. Even though she’s been training for two decades, Murphy considers herself still a student of traditional navigation. “We know what we do only because of Mau’s teachings,” she points out. “Nainoa combined Mau’s traditional knowledge with modern concepts to develop a method of wayfinding that worked for him.”

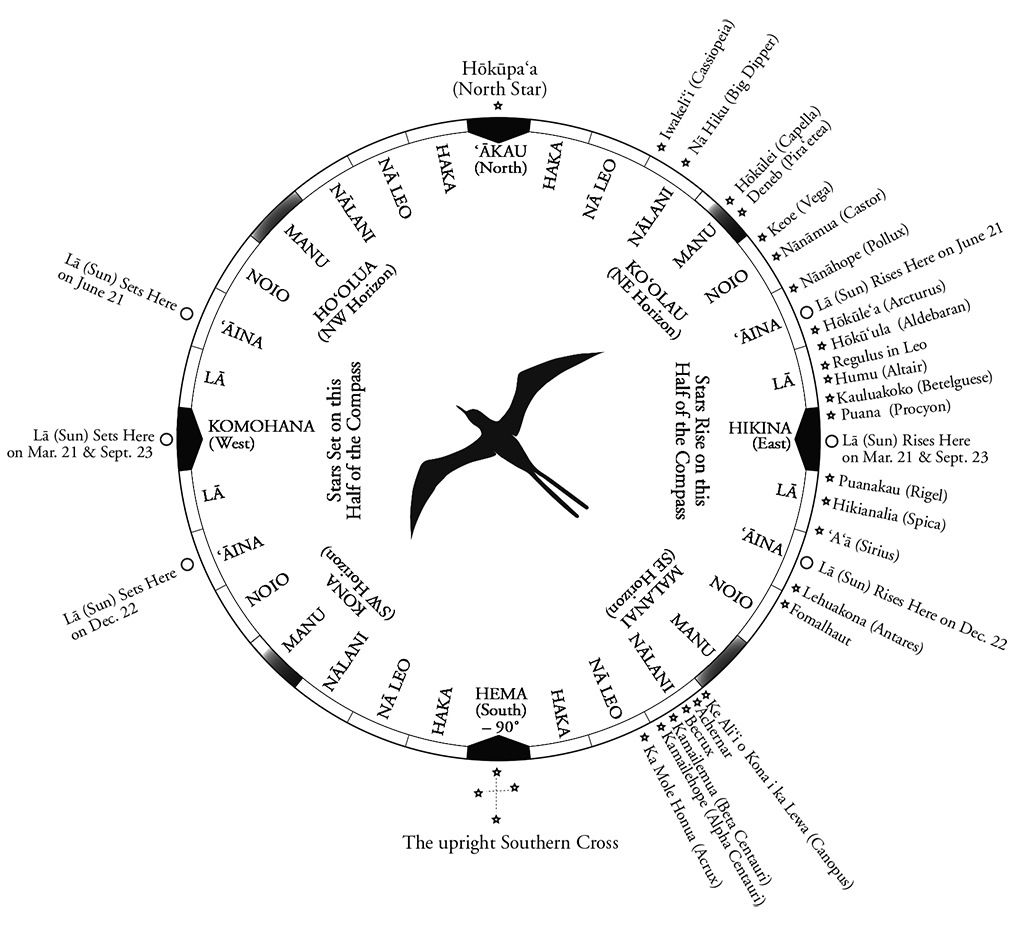

Traditional navigation involves memorizing more than 200 stars and knowing exactly where they’re rising on the horizon based on a 32-point sidereal star compass. “We know which house each star is rising and setting in, and we use those as directional clues. We also ‘pair’ stars that point to north and to south,” Murphy explains.

Navigators “calibrate” their hands so they can measure the height of the stars above the horizon to estimate the latitude. “When we plan a voyage, we plot a reference course, an imaginary line over the water, and every day we keep track of our position relative to that line,” Murphy says. “We must learn the sun’s and moon’s patterns to keep ourselves on course.”

Additionally, Murphy relies on ocean swells to determine the course. “When you can’t see the stars, which is most of the time, the swells are really our main clue,” she says. “You look at the direction the swells are coming from at sunrise and sunset.” Although these tools don’t allow navigators to measure longitude, the navigators can still steer toward a destination.

All this observation means navigators don’t get much sleep. “We estimate our position at every sunrise and sunset,” Murphy explains. “You need to be constantly observing — if you sleep too long, you can lose confidence.”

Traditional navigation holds great meaning for Murphy. “It’s such a special part of who and where we come from,” she says. It also evokes the epic comeback of Hawaiian culture from the low point it had reached before the canoes took to the seas again. “A few generations before me, parents didn’t teach children our native language because they’d been convinced it was not going to help in the future,” Murphy says. “Hawaiians were told we were lazy and just not very intelligent.”

But the Hokule’a changed all that. “The Hokule’a was a gift to the Hawaiian people,” says Low. “It taught them to find their way around the world.” And it taught them how to find their way back to their cultural heart.

— Nainoa Thompson, hokulea.com