Growing up in rural Washington State, Johnny Buck spent most of his time outside, on the banks of the Columbia River. Over the years, he began to notice that the traditional foods and plants his family and their community relied on were beginning to die off and experience extreme shifts in their growing seasons. It was these changes that pushed Buck to pursue a dream he didn’t even realize he had: researching plant phenology — the study of periodic biological phenomena in relation to climate conditions — to contribute to solving challenges around biodiversity.

Buck’s connection to the land is lifelong. As a member of the Wanapum Tribe on his father’s side and the Yakama Nation on his mother’s, Buck was steeped in tradition and respect for Mother Earth and the Creator at a young age. In his small indigenous community, the elders had never gone to school, but they and Buck’s parents felt strongly about education, and so Buck received traditional schooling through high school. Unfortunately, he didn’t receive the necessary support in high school to help him figure out his future plans.

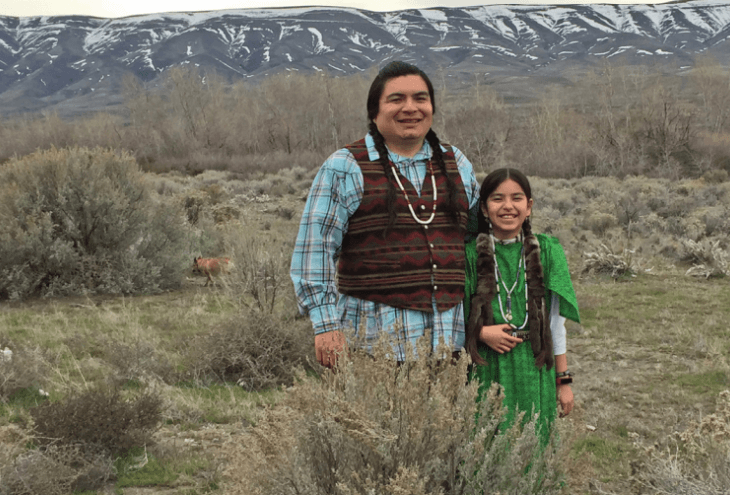

Buck was steeped in tradition and respect for Mother Earth and the Creator at a young age.

Luckily, Buck’s parents and elders encouraged him to live within his traditional culture. Buck agreed, and began spending his time shadowing the elders, his father, and his mother. “My goals at that time were to spend time with them and help strengthen my community and revitalize our traditional culture, language, and ceremonies,” he says. “My time with them motivated me to pursue the highest education.”

It was during this period that Buck became aware of changes in the growing seasons for native plants that were staple foods and medicines for the community. He noticed that growing seasons were beginning much later and becoming substantially shorter. The community was hard-hit by these changes, as members relied on various plants for their diet, traditions, culture, ceremonies, and medicines. Buck knew he wanted to help his community, and he soon realized how to do it.

In the fall of 2014, at the age of 36, Buck enrolled at Northwest Indian College to pursue a bachelor of science degree in Native environmental science. He is also part of the interdisciplinary concentration option, which allows him to work directly with faculty who share his research interests. The program is the only one of its kind in the nation. According to Buck, “It helps me strengthen who I am and identifies how I can contribute to solving challenges around biodiversity and indigenous traditional knowledge.”

His love for the program aside, college was a shock for Buck. As a first-generation college student, he didn’t know what to expect and had a difficult time adjusting. “Culture shock and homesick-ness were hard to get through,” he recalls. “My new culture was going to class, doing homework, and spending time behind a computer — a stark contrast to life in my village, where I was fishing and hunting most of the year.”

Buck also has the added responsibility of being the father of a young daughter. He made the difficult decision to relocate himself and his then seven-year-old daughter, Tatiwyat, to Northwest Indian College’s main campus. “I thought my academic goals were out of reach because of my responsibilities to provide for my daughter,” says Buck. “The move was essential to set myself up for academic success in a supportive, immersed environment.”

Having now finished his junior year, Buck has created a strong support network and become an integral part of the Northwest Indian College community. With another student he founded the Red Power club, whose mission is to “through education, promote and protect the holistic well-being of indigenous people and land.” Buck is also a member of AISES, and has found his experience with the organization — and more specifically his involvement with AISES’s Lighting the Pathway to Faculty Careers for Natives in STEM program — gratifying. “I’ve received support to pursue advanced degrees, and been able to work with peer mentors, including receiving mentor-ship from a distinguished Native faculty member who helps with professional development and advice,” he says.

Buck is taking the mentorship to heart, as he has accepted an offer from the 2017 Harvard Forest Summer Research Program in Ecology in Petersham, Mass., to work on a project explaining variation in the seasonal changes of trees. Buck is also considering applying to a PhD program in environmental engineering and a JD program focusing on environmental and Indian law. “My ultimate long-term academic career goal is to become a scientist, engineer, and attorney,” he says. “I hope to lead a team to study how we can protect, preserve, con-serve, and enhance our water supply. I will also lead this team in restoration efforts located on my ancestral homelands”

Between school, intern-ships, and his personal life, Buck is very busy. Nonetheless, the ways of the elders and his ancestors are always at the forefront of his thoughts. “My ancestors were visionaries, drummers, and dreamers,” he notes. Buck is now following his own dream, and he has some advice for others looking to follow theirs: “Prioritize your academics, and if you need help, find it — and always practice #FierceAndRadicalSelfLove.”