Wildfires are more intense than ever. In the past three years alone, hundreds of people lost their homes and many lost their lives due to massive blazes. There are mul- tiple reasons why fires are getting worse, but Laurel James, Yakama Nation, believes the fire suppression policy of the U.S. Forest Service is partly to blame.

Now the program manager for her tribe’s Wildlife, Vegetation, and Range Management Program, James is also an Interdisicplinary PhD candidate in both the School of Environmental & Forest Sciences and the Department of Anthropology at the University of Washington. She explains that the Yakama Nation is one of many western tribes that essentially fought fire with fire for thousands of years. James remembers how as people moved down from the hills when the first snow came, they set fires behind them — a practice that helps support future growth of valuable plants.

Changing Times

Knowledge of how fire renews the land has been passed down, but James says that government fire policies in the West were centered on suppression, not renewal.She attributes that policy to a catastrophic 1910 fire that burned 3 million acres in Idaho, Washington, and British Columbia. “Early fire policies of suppression changed the landscape for all tribes,” says James, explaining that people who managed tribal lands in those days were non-Natives with no knowledge of Indigenous culture.

Along with the recent upsurge in the severity of fires, James has noticed a change in the ability of the Yakama Nation, for one, to fight them. In the early 1990s, James recalls that the tribe had 20 eight-person fire crews. Today that number has dwindled, and fewer people are signing up.

Yakama Nation’s fire manager, Don Jones, agrees that resources are thin at a time when tribes are facing conflagrations. “I’ve seen a steady de- crease in funds for fire preparedness,” says Jones. Losing both resources and experienced firefighters creates challenges.

Changing Climate

But the greater challenge long term may be climate change. To counter it, Jones uses controlled burning, which he says is just one way to deal with more intense fires. “You really can’t burn the number of acres you need to burn to counter what climate change is throwing at us,” Jones explains.

Yakama Nation is only one of many tribes enlisting traditional knowledge to battle large fires and bring back cultural resources. Vernon Stearns, fuels manager for the Spokane Tribe in eastern Washington since 2003, spoke with elders about the tribe’s traditional use of fire to clear dead brush to prevent large wildfires and enhance the natural habitat. “Our foresters see the importance and the benefits that can produce,” he says, explaining that in 2015–2016 almost half the tribal lands burned in two large fires, prompting a review of land managment. “Although there were high-severity impacts, we did observe some low-severity impacts in areas we previously managed, especially where we used prescribed fire.

A hundred miles or so east, in the Montana Rockies, lies the Flathead Indian Reservation, where for thousands of years the Confederated Salish Kootenai Tribes (CSKT) set fires to shape the land, plants, and animals. In the documentary Fire on the Land, tribal elders describe how fire was part of a traditional way of life and what happens culturally when fires aren’t allowed to burn.

Fast-forward to today and fire managers are revitalizing controlled-burning techniques. Ron Swaney, Flathead Reservation fuels manager, says that burning has brought back traditional plants like camas, an important food for the tribe. There were “camas galore!” he says, after fire managers did a fuels treatment that opened the area and applied fire.

The Salish Kootenai have also seen a change in the intensity and magnitude of fires. “From 1980 until 2000, there were eight large fires. From 2000 until 2020, we’ve had 38 large fires,” Swaney says. He believes that hot summers make these large fires more likely while increasing the danger of controlled burning. “The more we get away from fire regimens, the m»ore fuel and debris accumulate to make more dramatic fires,” Swaney says. Adds James, “It’s hard to put fire back on the land when it’s not happened in a long time.”

The Bureau of Indian Affairs supports CSKT efforts to manage their land by using fires. Jim Durglo, fire technical specialist for the Intertribal Timber Council, says that “even the local government supports our activities. They see the benefit of what we’re doing.”

That support is critical if tribes are to avoid catastrophic fires in the future. But the ability to burn is not guaranteed. James is worried that this year’s mild winter will affect the landscape in the spring and fall months — the best time to burn — and she worries about future challenges from the changing climate. “It’s crazy,” she says, “how much change we are seeing in Mother Nature.”

Native Women Hotshots Step Up

Native Women Hotshots Step Up

Laurel James remembers her first experience working on a crew of hotshots — elite firefighters trained to battle intense wildfires. It was the summer of 1990 and she was just a few months into her job away from her tribe, the Yakama Nation. She and her fellow firefighters were sent to Arizona to help fight the Dude Fire, one of the most tragic in the history of the U.S. Forest Service.

The crew had started hiking back to dig lines when they were told to return to camp — six people on the prison inmate crew had lost their lives fighting the fire. She’d been on fires before, but this was a visceral experience. “That was a real moment for me,” James says. “I remember thinking, ‘this is what we do.’”

And more women are doing it. Still, women who fight wildland fires are rare — just 11 percent of Forest Service wildfire jobs are held by women, and the figure is lower in other firefighting agencies like the Bureau of Indian Affairs and Fish and Wildlife Service, where it’s closer to 6 percent.

Women hotshots are rarer still, but that is slowly changing. The BIA has been sponsoring Native hotshot crews since 1982, and currently funds seven, all of which are equal opportunity crews. As wildfires increase, so will the demand for both skilled men and women who have the knowledge to fight them.

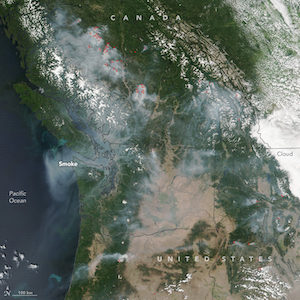

of the 2017 British Columbia wildfires.

First Nations Fire Management

In 2017, a mega-fire season devastated thick, lush forests in British Columbia and threatened settlements and towns. The flames also spurred a shift in public understanding of how climate change is affecting the frequency and intensity of forest fires.

The Yunesit’in and Xeni Gwet’in First Nations saw a warning in the fires that threatened their communities and began a plan to revitalize traditional fire management on the Tsilqot’in Traditional Territory. Last summer, after a year of consultation with elders and community members, their pilot project took off: they set fire to nearly 75 acres, guided by an Indigenous fire expert from Australia.

Recent studies show that incorporating Indigenous and local knowledge in land management schemes is key to strengthening bonds between humans and nature. Particularly in Canada, where public rhetoric and institutional policy have openly adopted measures to work toward “reconciliation,” fire management has come to the fore. Reconciliation, in this instance, means not only expanding decision- making powers, but questioning conceptions of what’s best when it comes to land health. This can often mean slight shifts in traditional definitions of sustainability and conservation, and a broader acceptance of what it may mean to protect nature itself: like letting it burn.

In Alberta, researchers are documenting cultural heritage and scientific data to better understand how fires were traditionally managed in the southern Rocky Mountains. Ontario’s Pikangikum First Nation is engaging elders and their oral histories in fire management planning for more than 3 million acres of boreal forest. The federal agency that manages Canada’s national parks is considering how best to “reunite” fire and landscape, and has credited Indigenous people with maintaining these systems before European settlers arrived. Still, adopting traditional knowledge into colonial systems may not go smoothly.

After their small controlled burn in the summer of 2019, the bands involved in the Tsilhqot’in pilot project reported new and resurging undergrowth where the fire licked, as well as an overall decrease in the amount of fuel that could ignite the next time fire nears. Their next steps will involve developing a system of carbon emissions monitoring, and implementing traditional wildfire management programs at a larger scale.

—by Lyndsie Bourgon