Native Hawaiian taro farmers inspired me to enter the 2017 AISES Energy Challenge, an energy-specific science fair that encourages high school students to get into STEM. Taro is a prized staple food and the root of Hawaiian culture. These farmers are off the grid because many of their patches are historical or cultural sites. I wanted to learn how byproducts from bacteria in the mud in their fields could provide them with a sustainable source of energy. I won the Grand Prize for designing a microbial fuel cell. Last year I won the prize again for my project on producing graphene for use in electronics.

My parents had different impacts on me in high school. My father, an electrical engineer who works in IT, inspired me to also become an electrical engineer. My mother made sure my work was well thought out and that I was punctual. Thanks to her example, I had enough discipline to keep my high school life intact and do my experiments.

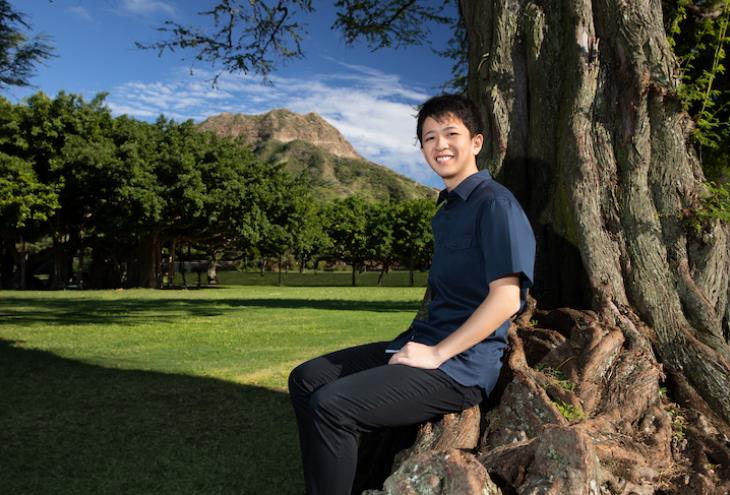

When I was a freshman at Kamehameha High School in Honolulu, I didn’t know high school students could do scientific research — I was only interested in playing snare drum in the marching band. But in my first year, I took Honors Biology, the most notoriously difficult freshman class. The next year my teacher got me interested in Honors Science Research. It wasn’t a popular class — only two other students in my grade signed up for it.

I’m super glad I made that choice because it got me into science research. I had to create my project ideas by researching current world problems and figuring out how to fix them. My teacher helped me design experiments, but when it came to performing them, she left me on my own. It was rough in the beginning. But after I did the experiments, processed the data, and wrote the report, I understood how to do it independently.

The thing I like most about STEM is being creative and innovative. When you do research, you touch topics on the edge of innovation — you’re trying to find things that haven’t existed before to help humanity.

I like the Hawaiian proverb Na-na- i ke kumu: look to the source. Our ancestors innovated by observing nature — by looking to the source. For students today Na-na- i ke kumu means look to our teachers, textbooks, and the internet as the source of knowledge.

I decided to go to the University of Portland because it’s a small school with an 11:1 student-faculty ratio. There’s almost no class where the professor isn’t able to help. As an incoming freshman, I found the community there very welcoming and the professors very supportive. You’re almost always able to find someone you know at the library and dining areas, or walking around the Bluff. For engineering and computer science majors, the recently renovated Shiley Hall offers a variety of resources, such as a maker space, computer lab, and metalworking shop.

Still, when I came to the mainland for college, the culture shock was pretty huge because of the differences in climate and people. There were definitely hardships with me being from Hawaii, a little rock in the Pacific. Thankfully, my transition was smoother than I expected, due to my science research background and the welcoming community. Many of my classes in math and science required understanding the scientific method, and my research experience helped me a lot my first year.

My best advice for anyone in high school is be creative. You want good grades, but being textbook smart will carry you only so far, so expand your experiences.

Another saying I live by is A’ohe pau ka ’ike i ka h’lau ho’okahi: all knowledge is not taught in one house. I consider a school a house (h’lau) that teaches us information. The world around us is the h’lau that teaches us how to gain knowledge ourselves. Look at everything as a learning experience and opportunity to grow.