AISES cofounder and former chairman Al Qöyawayma has an excellent “man cave” in his home in Prescott, Ariz., filled with a cozy clutter of art and books. Steve Jobs, who stares out from the cover of his biography, reflects some of Qöyawayma’s own ideas about success. “When we write resumes, we want to put in the good things,” Qöyawayma says. “Of course, it’s not always the good things you learn from.”

Qöyawayma knows mistakes made him stronger because he learned early on how to profit from them. “We’re all going to have failures,” he says, citing a popular question among recruiters: “What was your biggest failure and how did you handle it?” But he has a different question. “I want to know, if you had no other responsibilities, what would you be doing?” He says only a few people have thought about that, and to him those people are expressing a life goal. After all, he asks, what is all this studying and work for if not to help one another?

Growing up in Southern California, Qöyawayma was the only Indian on the block. “We played war and I always joined the cowboys!” he laughs. As a boy Qöyawayma’s father had attended Sherman Indian School, a government boarding school for Native Americans in Riverside, Calif., where he was forced to stop speaking his Hopi language and struggled with the imposed Anglo value system. Qöyawayma’s mother, a doctor, was part Cherokee. “I was an only child,” says Qöyawayma. “I didn’t have a village family.” As a result, Qöyawayma says, he became introverted and shy, but he was always figuring out how to get things done. “I’m an idea person,” he says. “I’m not someone who’s going to run things when they become methodical. Th at would bore me to death.”

In third grade he figured out how to navigate the Los Angeles bus and rail system. “I learned if I was willing to walk two miles I could save a nickel — enough to buy an ice cream,” he says. Then in sixth grade he discovered chemistry. “Back then they sold more complete chemistry sets,” he recalls. “And I wanted to make things that go boom!”

Despite his affinity for math and science, he describes himself as a “pretty average” student. What made the difference is how he approached challenges. “In junior high I had an English class and we had to write a skit and perform for two minutes. I was just petrified,” Qöyawayma says. But he knew that ultimately you’re going to have to work with other people, so he overcame his shyness and figured out how to work with his classmates.

That lesson helped him when he went to junior college and struggled in calculus. He found a classmate who wasn’t doing well in chemistry but was good in calculus, and offered to tutor him in chemistry in exchange for help with calculus. Between many shared pizzas that arrangement worked out well.

Through high school and college he earned money as an apprentice toolmaker being mentored in the expert use of every kind of precision machine tool. To finish his college degree, Qöyawayma chose to attend California Polytechnic State University in San Luis Obispo because the school emphasized “learn by doing.” He also chose to push himself. At Cal Poly the once-shy boy decided to run for an office in the college chapter of the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics. “I learned to speak,” he chuckles. “You’re going to have to learn to express your ideas. Th e other lesson is not to talk forever!”

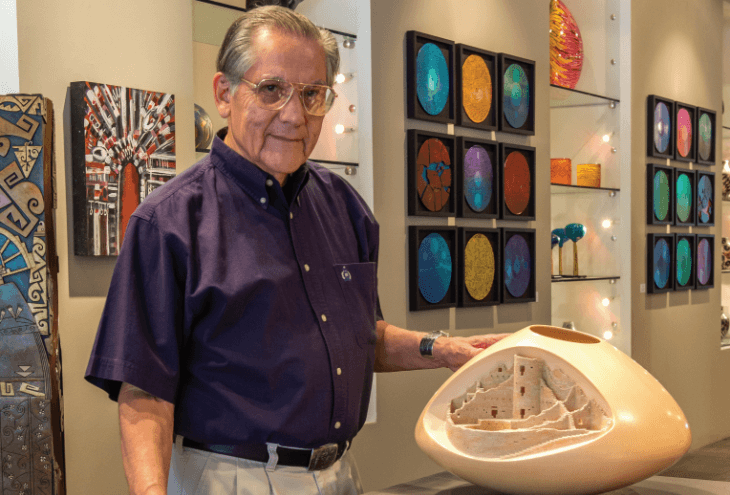

Ultimately Qöyawayma earned degrees in mechanical and systems engineering. He also educated himself in his Hopi heritage and found a new love, making pottery. In typical Qöyawayma fashion, he spent about three years first learning about clay. “Clay is really an interesting material,” he says, “from its liquid/soft state to a solid.” His “failures in the clay,” as he calls them, came about because he wanted to stretch the limits. (Read about the most recent of his many successes in clay on page 10.) HOPI The peaceful Hopi have maintained their language and traditions for centuries on Hopitukswa, a land of 1.5 million acres in northeastern Arizona.

In many ways clay is a metaphor for Qöyawayma’s life. It lets him feel, dream, and create. His aunt, mentor, and pottery teacher, Polingaysi Qöyawayma, also taught him the spiritual dimensions of the Creator’s most basic substance: clay. She taught him “the clay could help absorb tensions in life and to pray while you create.”

“The clay taught me another important lesson,” Qöyawayma adds. Cracking during the drying process was a problem, but one day he had an idea. “I gathered information on the diameters and angles in our ancient Hopi Sikyatki ceramics,” he says. “I noticed if you exceeded certain relationships the pot could crack.” His ancient relatives clearly knew there was a relationship. “They didn’t write it down,” Qöyawayma notes, but they left the record in their beautiful pieces. “Our ancestors understood how things worked in the natural world.”

His respect for indigenous knowledge is deep. “Our ancestors didn’t have textbooks, but they knew how to learn,” he says, citing as an example the Hopi technique of dry farming.

Qöyawayma has made a successful career in both engineering and the arts. Today he can afford to sit back and relax, sort of. “I like to read, particularly to follow new discoveries,” he says. “It’s a motivation to live another 30 years to find the answers to new, important questions.”

But make no mistake — Qöyawayma isn’t retired. He doesn’t believe in that. Rather, he seeks balance in his life, to serve others and learn more. “I can never learn enough,” he adds.