Logan Pallin, First Nation, grew up just outside the northern Minnesota community of Cloquet. Relatively rural, Cloquet has only about 10,000 residents, and Pallin spent much of his childhood exploring the surrounding forests and lakes.

Like many graduate students, he was drawn to science early on when he became involved in science fairs. “I just loved working on a project, figuring it out, and then having the opportunity to share it with the scientific community,” he says.

For middle school “science fair kids” like Pallin, the state science fair was the big leagues. “I’ll never forget when I got my first ticket to the Minnesota state science fair — and ended up winning a gold medal,” he says. “It was absolutely amazing.”

Pallin credits one of his middle school teachers, Dr. Cynthia Welsh, with playing a pivotal role in his interest in science. “Dr. Welsh became my science fair mentor in seventh grade, and continued to mentor me all the way through my senior year,” he says. “She traveled the country with me as I competed in national and international science competitions.” And Pallin did well: he was a gold medalist and finalist in 2009 at NAIVSEF (the National American Indian Virtual Science and Engineering Fair) in Albuquerque and at the 2010 Minnesota state competition in Minneapolis.

In high school, Pallin took as many college prep courses as he could. During a college-level calculus class, he got a surprising call from an academic coordinator at Duke University, inviting him to fly down to visit the Durham, N.C., campus. Once at Duke, he met with a financial aid advisor, who told him that his outstanding science work in high school would net him a full scholarship.

Like many freshmen, Pallin wasn’t entirely sure what he wanted to major in, but he began pursuing a degree in civil and environmental engineering and music.

After his freshman year, he even ventured to Italy for the summer to study music and composition. After he returned to campus, Pallin moved to the Duke University Marine Lab in Beaufort, N.C., where he was offered a chance to study marine mammals. “Everything just fell into place after that,” he says. “I’ve been studying marine mammals ever since. I had always been interested in marine life and aquatic ecosystems, and even spent seven months working on the Great Barrier Reef in Australia.”

Pallin has always been grateful for his supportive family, but especially during his transition from engineering to environmental science. “My parents have been my foundation through the best and hardest of times,” he says. “They have always told me that if I just did my best and worked hard, things would work out.”

And work out they did. Pallin earned his BS in environmental science with distinction, with a focus on marine conservation biology and a certificate in marine conservation and science leadership.

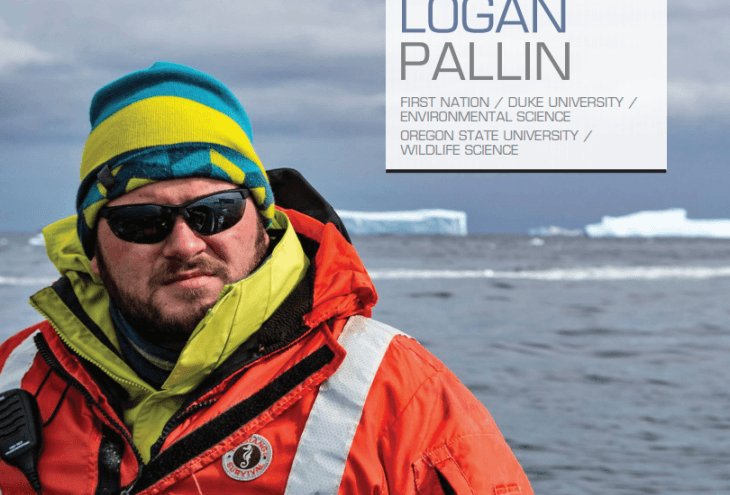

He is now in a master’s program in wildlife science, focusing on marine conservation biology, at Oregon State University. “A large part of my research revolves around traveling to the Antarctic and studying the population demographics of humpback whales along the Western Antarctic Peninsula, which lies under South America,” he explains.

Pallin plans to pursue a PhD with the goal of becoming a research professor, investigating cetacean population ecology, and inspiring the next generation of young scientists. To that end, he mentors undergraduates and gives them hands-on research and lab experience. “My team and I also actively engage with K–12 students and share our research with them,” he says. “Working with students is very important to me.”

And that includes today’s middle school students back in Cloquet. “I always like to go back to Dr. Welsh’s class and talk with her students,” he says. “I once even took two and a half months to work in her class every day. I want to inspire these students to develop their identities as scientists, and show them that they have opportunities to do amazing work outside of where they grow up.”

What Pallin has to teach those aspiring scientists goes way beyond marine biology. “I always tell students never to let anyone say they aren’t smart enough or that they can’t do something,” he emphasizes. “I was by no means the smartest kid in undergrad, but I had a deep passion for my work that allowed me to succeed — even in the most difficult of times.”