A typical eleventh-grader might spend Saturday hanging out with friends or playing sports. Marcy Ferriere spends her Saturdays crawling into abandoned wolf dens to gather data about these creatures’ habits. Some might find this strange — Ferriere finds it exhilarating.

Ferriere has loved growing up in her small town of Cloquet, Minn., with a population of just over 12,000. “You get to know everybody, and you’re not left out of anything,” she says. These connections created the foundation for her love of science, which started when she was in just seventh grade.

“We’re all required to do a seventh-grade science fair project,” she says. “I was working with zebra fish and their breathing and respiration rates. I fell in love with it.” Her work expanded beyond that science fair and went on for the next three years, with encouragement from her science teacher and science fair director, Dr. Cynthia Welsh.

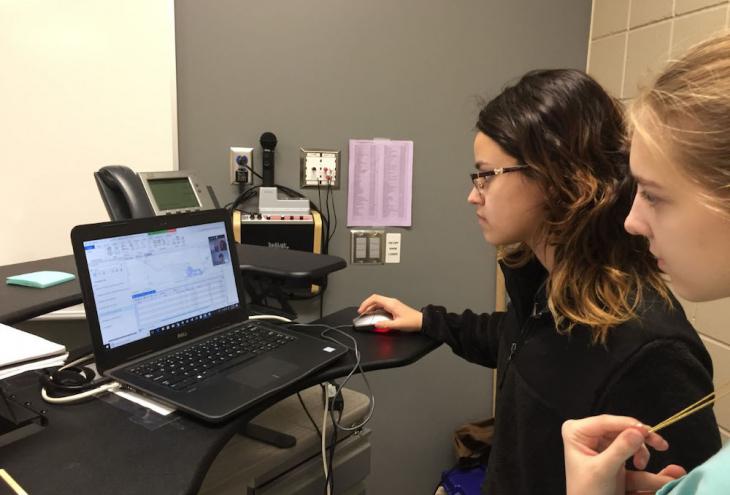

During the academic year, Ferriere [shown above, left, with her partner, Elizabeth Strickland] works on her project every day, and as she gets closer to competitions, she works on her project for up to six hours per day.

Three years later, when her work with zebra fish wasn’t eliciting the desired results, Ferriere knew where to turn. “I went to Dr. Welsh and asked if there was a project that would lead me a little bit further,” says Ferriere. “She recommended the wolf project and said we could use GIS mapping.”

Now Ferriere and her partner, Elizabeth Strickland, are studying three different wolf packs using GIS (geographic information system) mapping, which allows users to view their data as a map. Ferriere had never heard of GIS mapping before this project, but after using it, she plans to make it a focus of her future research. “I fell in love with GIS,” she says. “I can demand what I want it to be, how it looks, and what data I look for — I want to go into GIS mapping.”

As Ferriere and Strickland study natal and maternal dens to understand the wolves’ habits, GIS mapping is critical. “We’re figuring out why they put their dens where they do,” explains Ferriere. And while they gather the data, the program creates the visual map that allows them to understand what the data is showing.

But gathering that data was no easy feat. It was Ferriere, who describes herself as “thin and small,” who actually crawled inside the wolf dens to measure the various chambers. “I was a little nervous because we didn’t know what was going to be inside. I got stuck a couple of times!” she says. But her efforts were well worth it: she was able to obtain measurements that her team wouldn’t have been able to get otherwise.

Now, more than a year into the project, Ferriere and Strickland are piecing together the data and creating maps that tell an interesting story. “We looked at three different packs and their den positions. The dens are all about the same distance from every nearby road,” says Ferriere. “It’s almost as if the wolves know they have to be this certain distance from the road.”

measure the various chambers.

The findings weren’t exactly what Ferriere expected. “I thought the natal den — where the pups are born — was going to be farthest from human disturbances, but it wasn’t like that,” she explains. These findings have led Ferriere to want to expand her research. “We did only three dens out of 13 packs. I want to get more den points/locations, to see if there is a reason why they’re so far away from things like human disturbances and natural resources,” she adds.

It’s a tall order for a high school student who works on her science fair project after school and on weekends. During the academic year, Ferriere works on her project every day, and as she gets closer to competitions, she works on her project for up to six hours per day. The Northern Minnesota and American Indian Regional Science and Engineering Fair happens every February, and if you do well there, you can move on to the state science fair.

Science fair is such a big commitment that Ferriere recognizes she would never be able to make it work without a few key ingredients. “I do have a lot of support, not only with Dr. Welsh but with some of my teachers too,” she says. “My family is a really big support to me. My mom is my biggest support system.” That backup is key as Ferriere balances school and her project, especially when things don’t always go as planned. “There were a lot of times when we couldn’t get the mapping system to work, or we didn’t have enough data points to compute distances for where the wolves were traveling,” she says. “I was overwhelmed, but you just have to power through it.”

Ferriere credits her support system, stubborn nature, and desire to succeed for all she has accomplished. “When I set my mind to something, I have to get it done,” she says. “I want to show people that I’m capable of doing something meaningful, that I’m smart enough.”

Ferriere plans to continue work on GIS mapping with the wolf packs through the end of high school, and then has her sights set on studying GIS mapping in college. While Ferriere doesn’t know what she wants to do in the long term, she knows that you should never give up on your dream. “Keep trying because you don’t know where you’re going to end up,” she says. “I used to say I’d never like science fair, and here I am today, deeply in love with it.”